Hall James Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art 2nd Ed

| Saint John the Apostle | |

|---|---|

Stained glass of John the Apostle at St. Aidan's Cathedral, Enniscorthy | |

| Apostle and Evangelist | |

| Born | c. 6 AD [ane] Bethsaida, Galilee, Roman Empire |

| Died | c. 100 AD (aged 93–94) place unknown,[2] [3] probably Ephesus, Roman Empire[4] |

| Venerated in | All Christian denominations which venerate saints Islam (named as i of the disciples of Jesus)[5] |

| Canonized | Pre-congregation |

| Feast | 27 December (Roman Catholic, Anglican) 26 September (Eastern Orthodox) |

| Attributes | Book, a serpent in a chalice, cauldron, eagle |

| Patronage | Love, loyalty, friendships, authors, booksellers, burn-victims, poisonous substance-victims, art-dealers, editors, publishers, scribes, examinations, scholars, theologians, Turkey and Turks[six] |

| Influences | Jesus |

| Influenced | Ignatius of Antioch, Polycarp, Papias of Hierapolis, Odes of Solomon? [7] |

John the Apostle [8] (Ancient Greek: Ἰωάννης; Latin: Iohannes [9] c. 6 AD – c. 100 AD ) or Saint John the Dearest was 1 of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus according to the New Attestation. More often than not listed as the youngest apostle, he was the son of Zebedee and Salome. His brother was James, who was another of the Twelve Apostles. The Church Fathers identify him as John the Evangelist, John of Patmos, John the Elder, and the Beloved Disciple, and evidence that he outlived the remaining apostles and was the merely one to die of natural causes, although modern scholars are divided on the veracity of these claims.

John the Apostle is traditionally held to be the author of the Gospel of John, and many Christian denominations have also held that he was the author of several other books of the New Testament (the three Johannine epistles and the Book of Revelation, together with the Gospel of John called the Johannine works), depending on whether he is distinguished from or identified with John the Evangelist, John the Elder, and John of Patmos.

Although the authorship of the Johannine works has traditionally been attributed to John the Apostle,[10] only a minority of contemporary scholars believe he wrote the gospel,[eleven] and most conclude that he wrote none of them.[10] [12] [thirteen] Regardless of whether or not John the Apostle wrote any of the Johannine works, most scholars agree that all three epistles were written by the same writer and that the epistles did not take the same author as the Book of Revelation, although there is widespread disagreement among scholars every bit to whether the author of the epistles was different from that of the gospel.[14] [fifteen] [16]

References to John in the New Testament [edit]

John the Apostle was the son of Zebedee and the younger brother of James, son of Zebedee (James the Greater). According to church tradition, their mother was Salome.[17] [eighteen] Also according to some traditions, Salome was the sister of Mary, Jesus' mother,[18] [xix] making Salome Jesus' aunt, and her sons John the Apostle and James were Jesus' cousins.[20]

John the Apostle is traditionally believed to be one of ii disciples (the other being Andrew) recounted in John 1:35-39, who upon hearing the Baptist point out Jesus as the "Lamb of God," followed Jesus and spent the day with him. Thus, some traditions believe that he was showtime a disciple of John the Baptist, fifty-fifty though he is not named in this episode.[21]

According to the Synoptic Gospels (Matt 4:xviii-22; Mark 1:16-20; Lk 5:i-11), Zebedee and his sons fished in the Sea of Galilee. Jesus and then chosen Peter, Andrew and the ii sons of Zebedee to follow him. James and John are listed among the Twelve Apostles. Jesus referred to the pair equally "Boanerges" (translated "sons of thunder").[22] A Gospel story relates how the brothers wanted to call down heavenly fire on an unhospitable Samaritan boondocks, only Jesus rebuked them. [Lk ix:51-half-dozen] John lived on for another generation after the martyrdom of James, who was the offset Campaigner to die a martyr'southward death.

Other references to John [edit]

Peter, James and John were the only witnesses of the raising of the Daughter of Jairus.[23] All iii also witnessed the Transfiguration, and these aforementioned three witnessed the Agony in Gethsemane more closely than the other Apostles did.[24] John was the disciple who reported to Jesus that they had 'forbidden' a not-disciple from casting out demons in Jesus' name, prompting Jesus to state that 'he who is not confronting the states is on our side'.[25]

Jesus sent only John and Peter into the metropolis to make the preparation for the final Passover repast (the Last Supper).[Lk 22:eight] [26]

Many traditions identify the "honey disciple" in the Gospel of John as the Apostle John, only this identification is debated. At the repast itself, the "disciple whom Jesus loved" sabbatum side by side to Jesus. It was customary to recline on couches at meals, and this disciple leaned on Jesus.[24] Tradition identifies this disciple equally John.[Jn 13:23-25] Subsequently the arrest of Jesus, Peter and the "other disciple" (according to tradition, John) followed him into the palace of the high-priest.[24] The "dear disciple" alone, among the Apostles, remained virtually Jesus at the pes of the cross on Calvary aslope myrrhbearers and numerous other women. Following the pedagogy of Jesus from the Cantankerous, the honey disciple took Mary, the female parent of Jesus, into his care every bit the concluding legacy of Jesus.[Jn 19:25-27]

Subsequently Jesus' Ascension and the descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, John, together with Peter, took a prominent part in the founding and guidance of the church building. He was with Peter at the healing of the lame man at Solomon'due south Porch in the Temple[Acts 3:1 et seq.] and he was also thrown into prison with Peter.[Acts 4:three] He went with Peter to visit the newly converted believers in Samaria.[Acts 8:14]

While he remained in Judea and the surrounding area, the other disciples returned to Jerusalem for the Churchly Quango (about AD 51). Paul, in opposing his enemies in Galatia, recalls that John explicitly, forth with Peter and James the Just, were referred to every bit "pillars of the church" and refers to the recognition that his Apostolic preaching of a gospel free from Jewish Law received from these 3, the nigh prominent men of the messianic community at Jerusalem.[23]

The disciple whom Jesus loved [edit]

Jesus and the Beloved Disciple

The phrase "the disciple whom Jesus loved as a brother" ( ὁ μαθητὴς ὃν ἠγάπα ὁ Ἰησοῦς , ho mathētēs hon ēgapā ho Iēsous ), or in John 20:2; "whom Jesus loved equally a friend" ( ὃν ἐφίλει ὁ Ἰησοῦς , hon ephilei ho Iēsous ), is used half dozen times in the Gospel of John,[27] but in no other New Testament accounts of Jesus. John 21:24 claims that the Gospel of John is based on the written testimony of this disciple.

The disciple whom Jesus loved is referred to, specifically, six times in the Gospel of John:

- It is this disciple who, while reclining beside Jesus at the Last Supper, asks Jesus, after existence requested by Peter to do so, who it is that volition beguile him.[Jn xiii:23-25]

- Later at the crucifixion, Jesus tells his mother, "Woman, here is your son", and to the Beloved Disciple he says, "Hither is your mother."[Jn 19:26-27]

- When Mary Magdalene discovers the empty tomb, she runs to tell the Beloved Disciple and Peter. The two men rush to the empty tomb and the Beloved Disciple is the first to reach the empty tomb. Withal, Peter is the first to enter.[Jn xx:1-ten]

- In John 21, the last chapter of the Gospel of John, the Dearest Disciple is 1 of seven fishermen involved in the miraculous catch of 153 fish.[Jn 21:1-25] [28]

- Likewise in the volume's final chapter, after Jesus hints to Peter how Peter will die, Peter sees the Beloved Disciple following them and asks, "What about him?" Jesus answers, "If I want him to remain until I come, what is that to you lot? Yous follow Me!"[John 21:20-23]

- Once again in the Gospel's concluding affiliate, it states that the very volume itself is based on the written testimony of the disciple whom Jesus loved.[John 21:24]

None of the other Gospels has anyone in the parallel scenes that could exist directly understood as the Dearest Disciple. For example, in Luke 24:12, Peter alone runs to the tomb. Marking, Matthew and Luke do not mention whatever i of the twelve disciples having witnessed the crucifixion.

There are besides 2 references to an unnamed "other disciple" in John one:35-twoscore and John 18:fifteen-16, which may be to the same person based on the wording in John twenty:2.[29]

[edit]

Lamentation of the Virgin. John the Apostle trying to console Mary, 1435

Church tradition has held that John is the author of the Gospel of John and four other books of the New Testament – the iii Epistles of John and the Book of Revelation. In the Gospel, authorship is internally credited to the "disciple whom Jesus loved" ( ὁ μαθητὴς ὃν ἠγάπα ὁ Ἰησοῦς , o mathētēs on ēgapa o Iēsous) in John 20:2. John 21:24 claims that the Gospel of John is based on the written testimony of the "Honey Disciple". The authorship of some Johannine literature has been debated since about the year 200.[30] [31]

In his Ecclesiastical History, Eusebius says that the First Epistle of John and the Gospel of John are widely agreed upon equally his. However, Eusebius mentions that the consensus is that the 2d and 3rd epistles of John are not his but were written by some other John. Eusebius also goes to some length to plant with the reader that there is no general consensus regarding the revelation of John. The revelation of John could only be what is now called the Book of Revelation.[32] The Gospel co-ordinate to John differs considerably from the Synoptic Gospels, which were probable written decades earlier. The bishops of Asia Minor supposedly requested him to write his gospel to bargain with the heresy of the Ebionites, who asserted that Christ did not exist before Mary. John probably knew of the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, but these gospels spoke of Jesus primarily in the twelvemonth following the imprisonment and death of John the Baptist.[33] Around 600, however, Sophronius of Jerusalem noted that "two epistles begetting his name ... are considered by some to exist the work of a certain John the Elder" and, while stating that Revelation was written by John of Patmos, it was "later translated past Justin Martyr and Irenaeus,"[i] presumably in an attempt to reconcile tradition with the obvious differences in Greek mode.

Until the 19th century, the authorship of the Gospel of John had been attributed to the Apostle John. However, nigh modern disquisitional scholars accept their doubts.[34] Some scholars identify the Gospel of John somewhere between Advert 65 and 85;[35] [ page needed ] John Robinson proposes an initial edition by 50–55 and so a last edition by 65 due to narrative similarities with Paul.[36] : pp.284, 307 Other scholars are of the opinion that the Gospel of John was composed in two or three stages.[37] : p.43 Most contemporary scholars consider that the Gospel was not written until the latter third of the kickoff century AD, and with the earliest possible date of Advertising 75-fourscore: "...a engagement of AD 75-80 as the earliest possible appointment of composition for this Gospel."[38] Other scholars think that an even afterward date, perchance fifty-fifty the last decade of the first century AD right upwardly to the start of the 2d century (i.due east. 90 - 100), is applicable.[39]

Nonetheless, today many theological scholars proceed to accept the traditional authorship. Colin G. Kruse states that since John the Evangelist has been named consistently in the writings of early Church Fathers, "it is hard to laissez passer by this conclusion, despite widespread reluctance to accept it past many, but by no ways all, modern scholars."[40]

Modern, mainstream Bible scholars by and large affirm that the Gospel of John has been written by an anonymous author.[41] [42] [43]

Regarding whether the writer of the Gospel of John was an eyewitness, according to Paul N. Anderson, the gospel "contains more direct claims to eyewitness origins than any of the other Gospel traditions."[44] F. F. Bruce argues that 19:35 contains an "emphatic and explicit claim to eyewitness authorization."[45] The gospel nowhere claims to have been written by direct witnesses to the reported events.[43] [46] [47]

Mainstream Bible scholars affirm that all four gospels from the New Testament are fundamentally bearding and most of mainstream scholars hold that these gospels have non been written past eyewitnesses.[48] [49] [50] [51] Equally The New Oxford Annotated Bible (2018) has put it, "Scholars generally hold that the Gospels were written 40 to threescore years after the death of Jesus."[51]

Book of Revelation [edit]

According to the Book of Revelation, its author was on the island of Patmos "for the word of God and for the testimony of Jesus", when he was honoured with the vision contained in Revelation.[Rev. 1:nine]

The author of the Book of Revelation identifies himself as "Ἰωάννης" ("John" in standard English translation).[52] The early on second century writer, Justin Martyr, was the first to equate the writer of Revelation with John the Campaigner.[53] However, most biblical scholars now contend that these were separate individuals since the text was written effectually 100 Advertizement, after the death of John the Campaigner,[34] [54] [55] although many historians have defended the identification of the Author of the Gospel of John with that of the Book of Revelation based on the similarity of the ii texts.[56]

John the Presbyter, an obscure figure in the early church building, has also been identified with the seer of the Book of Revelation by such authors every bit Eusebius in his Church History (Book III, 39) [55] and Jerome.[57]

John is considered to have been exiled to Patmos, during the persecutions under Emperor Domitian. Revelation 1:9 says that the author wrote the book on Patmos: "I, John, both your brother and companion in tribulation, ... was on the isle that is called Patmos for the word of God and for the testimony of Jesus Christ." Adela Yarbro Collins, a biblical scholar at Yale Divinity School, writes:

Early tradition says that John was banished to Patmos by the Roman authorities. This tradition is credible considering adjournment was a common penalization used during the Imperial period for a number of offenses. Among such offenses were the practices of magic and astrology. Prophecy was viewed by the Romans every bit belonging to the same category, whether Pagan, Jewish, or Christian. Prophecy with political implications, like that expressed by John in the book of Revelation, would take been perceived as a threat to Roman political power and order. Three of the islands in the Sporades were places where political offenders were banished. (Pliny Natural History four.69-70; Tacitus Register 4.thirty)[58]

Some modern disquisitional scholars have raised the possibility that John the Apostle, John the Evangelist, and John of Patmos were three divide individuals.[59] These scholars assert that John of Patmos wrote Revelation but neither the Gospel of John nor the Epistles of John. The author of Revelation identifies himself every bit "John" several times, but the writer of the Gospel of John never identifies himself directly. Some Catholic scholars state that "vocabulary, grammar, and style arrive doubtful that the book could have been put into its present form past the same person(south) responsible for the quaternary gospel."[60]

[edit]

Print of John the Apostle made at ca. the end of the 16th c. - the beginning of the 17th c.[61]

At that place is no information in the Bible concerning the duration of John's activeness in Judea. According to tradition, John and the other Apostles remained some 12 years in this offset field of labour. The persecution of Christians under Herod Agrippa I (r. 41-44 AD) led to the scattering of the Apostles through the Roman Empire'due south provinces.[cf. Air conditioning 12:1-17]

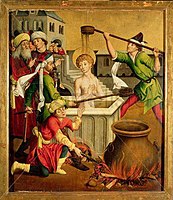

A messianic community existed at Ephesus before Paul'south beginning labors at that place (cf. "the brethren"),[Acts 18:27] in add-on to Priscilla and Aquila. The original community was under the leadership of Apollos (1 Corinthians ane:12). They were disciples of John the Baptist and were converted by Aquila and Priscilla.[62] According to tradition, after the Assumption of Mary, John went to Ephesus. Irenaeus writes of "the church of Ephesus, founded by Paul, with John continuing with them until the times of Trajan."[63] From Ephesus he wrote the 3 epistles attributed to him. John was allegedly banished by the Roman authorities to the Greek island of Patmos, where, according to tradition, he wrote the Book of Revelation. Co-ordinate to Tertullian (in The Prescription of Heretics) John was banished (presumably to Patmos) after being plunged into boiling oil in Rome and suffering nothing from it. Information technology is said that all in the audition of Colosseum were converted to Christianity upon witnessing this miracle. This outcome would have occurred in the belatedly 1st century, during the reign of the Emperor Domitian, who was known for his persecution of Christians.

When John was anile, he trained Polycarp who later became Bishop of Smyrna. This was important because Polycarp was able to acquit John's message to future generations. Polycarp taught Irenaeus, passing on to him stories almost John. Similarly, Ignatius of Antioch was a student of John. In Against Heresies, Irenaeus relates how Polycarp told a story of

John, the disciple of the Lord, going to bathe at Ephesus, and perceiving Cerinthus within, rushed out of the bath-house without bathing, exclaiming, "Permit united states of america wing, lest fifty-fifty the bath-house fall down, because Cerinthus, the enemy of the truth, is inside."[64]

It is traditionally believed that John was the youngest of the apostles and survived them. He is said to have lived to old age, dying at Ephesus erstwhile after AD 98, during the reign of Trajan.[65]

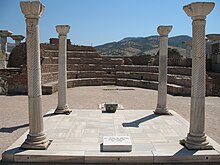

An culling account of John's death, ascribed by afterward Christian writers to the early on second-century bishop Papias of Hierapolis, claims that he was slain by the Jews.[66] [67] Most Johannine scholars doubt the reliability of its ascription to Papias, merely a minority, including B.West. Bacon, Martin Hengel and Henry Barclay Swete, maintain that these references to Papias are credible.[68] [69] Zahn argues that this reference is actually to John the Baptist.[65] John's traditional tomb is thought to be located in the former basilica of Saint John at Selçuk, a small town in the vicinity of Ephesus.[70]

John is as well associated with the pseudepigraphal apocryphal text of the Acts of John, which is traditionally viewed as written past John himself or his disciple, Leucius Charinus. Information technology was widely circulated past the 2d century CE but deemed heretical at the Second Quango of Nicaea (787 CE). Varying fragments survived in Greek and Latin within monastic libraries. It contains strong docetic themes, but is not considered in modernistic scholarship to be Gnostic.[71] [72]

Liturgical celebration [edit]

The feast twenty-four hours of Saint John in the Roman Catholic Church, which calls him "Saint John, Apostle and Evangelist", and in the Anglican Communion and Lutheran Calendars, which phone call him "Saint John the Apostle and Evangelist", is on 27 December.[73] In the Tridentine Calendar he was commemorated also on each of the following days up to and including 3 January, the Octave of the 27 December banquet. This Octave was abolished by Pope Pius XII in 1955.[74] The traditional liturgical color is white. John, Campaigner and Evangelist is remembered in the Church of England with a Festival on 27 December.[75]

Until 1960, another banquet day which appeared in the General Roman Agenda is that of "Saint John Earlier the Latin Gate" on 6 May, celebrating a tradition recounted by Jerome that St John was brought to Rome during the reign of the Emperor Domitian, and was thrown in a vat of boiling oil, from which he was miraculously preserved unharmed. A church (San Giovanni a Porta Latina) defended to him was built nigh the Latin gate of Rome, the traditional site of this consequence.[76]

The Eastern Orthodox Church building and those Eastern Catholic Churches which follow the Byzantine Rite commemorate the "Repose of the Holy Apostle and Evangelist John the Theologian" on 26 September. On 8 May they celebrate the "Feast of the Holy Campaigner and Evangelist John the Theologian", on which date Christians used to draw forth from his grave fine ashes which were believed to be effective for healing the sick.

Other views [edit]

Islamic view [edit]

The Quran besides speaks of Jesus's disciples just does not mention their names, instead referring to them every bit "supporters for [the crusade of] Allah".[77] The Sunnah did not mention their names either. Nonetheless, some Muslim scholars mentioned their names,[78] likely relying on the resource of Christians, who are considered "People of the Book" in Islamic tradition. Muslim exegesis more-or-less agrees with the New Testament list and says that the disciples included Peter, Philip, Thomas, Bartholomew, Matthew, Andrew, James, Jude, John and Simon the Zealot.[79] Notably, narrations of People of the Volume (Christians and Jews) are not to be believed or disbelieved by Muslims equally long every bit at that place is nothing that supports or denies them in Quran or Sunnah.[80]

Latter-day Saint view [edit]

The Church building of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church building) teaches that, "John is mentioned frequently in latter-day revelation (1 Ne. 14:18–27; iii Ne. 28:6; Ether four:16; D&C 7; 27:12; 61:14; 77; 88:141). For Latter-day Saints these passages confirm the biblical tape of John and besides provide insight into his greatness and the importance of the piece of work the Lord has given him to do on the earth in New Testament times and in the last days. The latter-solar day scriptures clarify that John did not die but was allowed to remain on the globe as a ministering retainer until the fourth dimension of the Lord'southward Second Coming (John 21:20–23; 3 Ne. 28:6–7; D&C seven)".[81] It also teaches that in 1829, forth with the resurrected Peter and the resurrected James, John visited Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery and restored the priesthood dominance with Apostolic succession to globe.[82] John, along with the Iii Nephites, will live to come across the 2nd Coming of Christ as translated beings.[83]

The LDS Church building teaches that John the Apostle is the same person every bit John the Evangelist, John of Patmos, and the Beloved Disciple.[83]

In fine art [edit]

As he was traditionally identified with the beloved campaigner, the evangelist, and the author of the Revelation and several Epistles, John played an extremely prominent office in art from the early Christian menses onward.[84] He is traditionally depicted in one of ii distinct ways: either equally an anile human with a white or greyness beard, or alternatively as a beardless youth.[85] [86] The kickoff way of depicting him was more common in Byzantine art, where it was possibly influenced past antiquarian depictions of Socrates;[87] the second was more mutual in the art of Medieval Western Europe, and can exist dated back equally far every bit 4th century Rome.[86]

Legends from the Acts of John, an apocryphal text attributed to John, contributed much to Medieval iconography; information technology is the source of the thought that John became an campaigner at a immature age.[86] Ane of John's familiar attributes is the chalice, frequently with a serpent emerging from it.[84] This symbol is interpreted equally a reference to a legend from the Acts of John,[88] in which John was challenged to drink a cup of poison to demonstrate the power of his faith (the poison beingness symbolized by the serpent).[84] Other common attributes include a book or scroll, in reference to the writings traditionally attributed to him, and an eagle,[86] which is argued to symbolize the loftier-soaring, inspirational quality of these writings.[84]

In Medieval and through to Renaissance works of painting, sculpture and literature, Saint John is oft presented in an androgynous or feminized style.[89] Historians have related such portrayals to the circumstances of the believers for whom they were intended.[90] For instance, John's feminine features are argued to accept helped to make him more relatable to women.[91] As well, Sarah McNamer argues that considering of his status equally an androgynous saint, John could office as an "image of a third or mixed gender"[92] and "a crucial figure with whom to place"[93] for male person believers who sought to cultivate an attitude of affective piety, a highly emotional manner of devotion that, in belatedly-medieval civilisation, was thought to exist poorly compatible with masculinity.[94] After the Heart Ages, feminizing portrayals of Saint John continued to be made; a instance in indicate is an etching past Jacques Bellange, shown to the correct, described by fine art critic Richard Dorment equally depicting "a softly androgynous beast with a corona of frizzy hair, modest breasts similar a teenage girl, and the round belly of a mature woman."[95]

In the realm of popular media, this latter phenomenon was brought to notice in Dan Dark-brown'southward novel The Da Vinci Code (2003), where i of the volume'southward characters suggests that the feminine-looking person to Jesus' right in Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper is actually Mary Magdalene rather than St. John.

Gallery of fine art [edit]

- John the Apostle

-

-

Martyrdom of Saint John the Evangelist by Master of the Winkler Epitaph

-

-

Saint John and the Poisoned Cup by El Greco, c. 1610-1614

-

The Final Supper, anonymous painter

See also [edit]

- Basilica of St. John

- Iv evangelists

- List of biblical figures identified in extra-biblical sources

- Names of John

- St. John the Evangelist on Patmos

- Vision of St. John on Patmos, 1520-1522 frescos by Antonio da Correggio

- Acts of John, a pseudepigraphal account of John's miracle work

- Saint John the Apostle, patron saint archive

References [edit]

- ^ a b Saint Sophronius of Jerusalem (2007) [c. 600], "The Life of the Evangelist John", The Caption of the Holy Gospel Co-ordinate to John, House Springs, Missouri, Us: Chrysostom Printing, pp. 2–3, ISBN978-1-889814-09-4

- ^ Wills, Garry (10 March 2015). The Futurity of the Catholic Church with Pope Francis. Penguin Publishing Grouping. p. 49. ISBN978-0-698-15765-1.

(Candida Moss marshals the historical bear witness to prove that "we only don't know how whatsoever of the apostles died, much less whether they were martyred.")six

Citing Moss, Candida (5 March 2013). The Myth of Persecution: How Early Christians Invented a Story of Martyrdom. HarperCollins. p. 136. ISBN978-0-06-210454-0. - ^

Nor do we have reliable accounts from afterwards times. What nosotros have are legends, about some of the apostles – importantly Peter, Paul, Thomas, Andrew, and John. Simply the apocryphal Acts that tell their stories are indeed highly apocryphal.

—Bart D. Ehrman, "Were the Disciples Martyred for Believing the Resurrection? A Smash From the By", ehrmanblog.org

"The big problem with this argument [of who would die for a lie] is that it assumes precisely what nosotros don't know. We don't know how most of the disciples died. The side by side time someone tells you lot they were all martyred, inquire them how they know. Or ameliorate nonetheless, inquire them which ancient source they are referring to that says so. The reality is [that] we simply do not take reliable information nearly what happened to Jesus' disciples after he died. In fact, nosotros scarcely accept whatsoever information nigh them while they were nevertheless living, nor do nosotros have reliable accounts from later on times. What we have are legends."

—Bart Ehrman, Emerson Dark-green, "Who Would Dice for a Prevarication?"

- ^ Kurian, George Thomas; Smith, Iii, James D. (2010). The Encyclopedia of Christian Literature, Volume 2. Scarecrow Printing. p. 391. ISBN9780810872837.

Though not in complete agreement, near scholars believe that John died of natural causes in Ephesus

- ^ Historical Dictionary of Prophets In Islam And Judaism, Brandon One thousand. Wheeler, Disciples of Christ: "Islam identifies the disciples of Jesus as Peter, Philip, Andrew, Matthew, Thomas, John, James, Bartholomew, and Simon"

- ^ P. Foley, Michael (2020). Drinking with Your Patron Saints: The Sinner's Guide to Honoring Namesakes and Protectors. Simon and Schuster. p. 150. ISBN9781684510474.

John is a patron saint of Asia Pocket-size and Turkey and Turks considering of his missionary piece of work there.

- ^ Smith, Preserved (1915). "The Disciples of John and the Odes of Solomon" (PDF). The Monist. 25 (2): 161–199. doi:10.5840/monist191525235. JSTOR 27900527. Retrieved ten April 2022.

- ^ "Saint John the Apostle". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016.

- ^ Also Aramaic: ܝܘܚܢܢ ܫܠܝܚܐ, Yohanān Shliḥā ; Hebrew: יוחנן בן זבדי, Yohanan ben Zavdi ; Coptic: ⲓⲱⲁⲛⲛⲏⲥ or ⲓⲱ̅ⲁ [ commendation needed ]

- ^ a b Harris, Stephen L. (1985). Understanding the Bible: a Reader's Introduction (2nd ed.). Palo Alto: Mayfield. p. 355. ISBN978-0-87484-696-half dozen.

Although ancient traditions attributed to the Apostle John the Quaternary Gospel, the Book of Revelation, and the three Epistles of John, modern scholars believe that he wrote none of them.

- ^ Lindars, Edwards & Courtroom 2000, p. 41.

- ^ Kelly, Joseph F. (i Oct 2012). History and Heresy: How Historical Forces Can Create Doctrinal Conflicts. Liturgical Press. p. 115. ISBN978-0-8146-5999-one.

- ^ Harris, Stephen L. (1980). Understanding the Bible: A Reader'southward Guide and Reference. Mayfield Publishing Company. p. 296. ISBN978-0-87484-472-6 . Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ^ Kruger, Michael J. (xxx April 2012). My library My History Books on Google Play Canon Revisited: Establishing the Origins and Authority of the New Testament Books. p. 272. ISBN9781433530814.

- ^ Brown, Raymond E. (1988). The Gospel and Epistles of John: A Curtailed Commentary. p. 105. ISBN9780814612835.

- ^ Marshall, I. Howard (fourteen July 1978). The Epistles of John. ISBN9781467422321.

- ^ by comparison Matthew 27:56 to Mark 15:40

- ^ a b "Topical Bible: Salome". biblehub.com . Retrieved seven August 2020.

- ^ "John 19 Commentary - William Barclay'south Daily Study Bible". StudyLight.org . Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ "The Disciples of Our Saviour". biblehub.com . Retrieved 7 Baronial 2020.

- ^ "John, The Apostle - International Standard Bible Encyclopedia". Bible Report Tools . Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ^ Media, Franciscan (27 December 2015). "Saint John the Campaigner".

- ^ a b "Fonck, Leopold. "St. John the Evangelist." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 6 Feb. 2013". Newadvent.org. 1 October 1910. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ a b c "St John The Evangelist". www.ewtn.com.

- ^ Luke 9:49-50 NKJV

- ^ While Luke states that this is the Passover,[Lk 22:7-9] the Gospel of John specifically states that the Passover meal occurs on the post-obit day[Jn eighteen:28]

- ^ John 13:23, 19:26, twenty:2, 21:7, 21:twenty, 21:24

- ^ James D. K. Dunn and John William Rogerson, Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2003, p. 1210, ISBN 0-8028-3711-5.

- ^ Brown, Raymond Eastward. 1970. "The Gospel According to John (xiii-xxi)". New York: Doubleday & Co. Pages 922, 955

- ^ Eusebius of Caesarea, Ecclesiastical History Book six. Chapter xxv.

- ^ "Cosmic ENCYCLOPEDIA: Apocalypse".

- ^ The History of the Church by Eusibius. Volume 3, point 24.

- ^ Thomas Patrick Halton, On illustrious men, Volume 100 of The Fathers of the Church, CUA Press, 1999. P. xix.

- ^ a b Harris, Stephen L., Agreement the Bible (Palo Alto: Mayfield, 1985) p. 355

- ^ Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. McGraw-Hill, 2006. ISBN 978-0-07-296548-iii

- ^ Robinson, John A.T. (1977). Redating the New Testament. SCM Printing. ISBN978-0-334-02300-v.

- ^ Mark Allan Powell. Jesus equally a figure in history. Westminster John Knox Press, 1998. ISBN 0-664-25703-8 / 978-0664257033

- ^ Gail R. O'Twenty-four hours, introduction to the Gospel of John in New Revised Standard Translation of the Bible, Abingdon Printing, Nashville, 2003, p.1906

- ^ Reading John, Francis J. Moloney, SDB, Dove Press, 1995

- ^ Kruse, Colin G.The Gospel Co-ordinate to John: An Introduction and Commentary, Eerdmans, 2004, ISBN 0-8028-2771-3, p. 28.

- ^ E P Sanders, The Historical Effigy of Jesus, (Penguin, 1995) page 63 - 64.

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman (2000:43) The New Testament: a historical introduction to early Christian writings. Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b Bart D. Ehrman (2005:235) Lost Christianities: the battles for scripture and the faiths we never knew Oxford Academy Printing, New York.

- ^ Paul Due north. Anderson, The Riddles of the Fourth Gospel, p. 48.

- ^ F. F. Bruce, The Gospel of John, p. three.

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman (2004:110) Truth and Fiction in The Da Vinci Code: A Historian Reveals What We Really Know nearly Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and Constantine. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman(2006:143) The lost Gospel of Judas Iscariot: a new expect at betrayer and betrayed. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Millard, Alan (2006). "Authors, Books, and Readers in the Ancient Globe". In Rogerson, J.W.; Lieu, Judith Thousand. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Biblical Studies. Oxford University Printing. p. 558. ISBN978-0199254255.

The historical narratives, the Gospels and Acts, are anonymous, the attributions to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John being first reported in the mid-second century by Irenaeus

- ^ Blood-red 2011, pp. thirteen, 42.

- ^ Perkins & Coogan 2010, p. 1380.

- ^ a b Coogan et al. 2018, p. 1380.

- ^ "Revelation, Book of." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho, 81.4

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D. (2004). The New Attestation: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings. New York: Oxford. p. 468. ISBN0-nineteen-515462-two.

- ^ a b "Church History, Book 3, Affiliate 39". The Fathers of the Church building. NewAdvent.org. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ Wagner, Richard; Helyer, Larry R. (2011). The Volume of Revelation For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 26. ISBN9781118050866.

other contemporary scholars have vigorously defended the traditional view of apostolic authorship.

- ^ saint, Jerome. "De Viris Illustribus (On Illustrious Men) Affiliate 9 & 18". newadvent.org. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ Adela Collins. "Patmos." Harper's Bible Dictionary. Paul J. Achtemeier, gen. ed. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1985. p755.

- ^ Griggs, C. Wilfred. "John the Beloved" in Ludlow, Daniel H., ed. Selections from the Encyclopedia of Mormonism: Scriptures of the Church (Salt Lake Urban center, Utah: Deseret Volume, 1992) p. 379. Griggs favors the "ane John" theory but mentions that some modern scholars have hypothesized that at that place are multiple Johns.

- ^ Introduction. Saint Joseph Edition of the New American Bible: Translated from the Original Languages with Critical Use of All the Ancient Sources: including the Revised New Testament and the Revised Psalms. New York: Catholic Book Pub., 1992. 386. Print.

- ^ "Heilige Johannes". lib.ugent.be . Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ Vailhé, Siméon (6 February 2013) [New York: Robert Appleton Co., 1909-5-1]. "Ephesus". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 5. New appearance. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ Grant, Robert M. (1997). Irenaeus of Lyons. London: Routledge. p. two.

- ^ Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 3.three.4.

- ^ a b "John the Campaigner". CCEL.

- ^ Cheyne, Thomas Kelly (1901). "John, Son of Zebedee". Encyclopaedia Biblica. Vol. two. Adam & Charles Black. pp. 2509–11. Although Papias' works are no longer extant, the 5th-century ecclesiastical historian Philip of Side and the ninth-century monk George Hamartolos both stated that Papias had written that John was "slain by the Jews."

- ^ Rasimus, Tuomas (2010). The Legacy of John: 2nd-Century Reception of the Fourth Gospel. Brill. p. five. ISBN978-9-00417633-1. Rasimus finds corroborating evidence for this tradition in "two martyrologies from Edessa and Carthage" and writes that "Mark ten:35–40//Matt. 20:20–23 can be taken to portray Jesus predicting the martyrdom of both the sons of Zebedee."

- ^ Culpepper, R. Alan (2000). John, the Son of Zebedee: The Life of A Legend. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 172. ISBN9780567087423.

- ^ Swete, Henry Barclay (1911). The Apocalypse of St. John (3 ed.). Macmillan. pp. 179–180.

- ^ Procopius of Caesarea, On Buildings. General Index, trans. H. B. Dewing and Glanville Downey, vol. vii, Loeb Classical Library 343 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Academy Press, 1940), 319

- ^ "The Acts of John". gnosis.org . Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ Lost scriptures : books that did not brand it into the New Attestation . Ehrman, Bart D. New York: Oxford University Press. 2003. ISBN0195141822. OCLC 51886442.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "The Calendar". xvi October 2013.

- ^ General Roman Calendar of Pope Pius XII

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church building of England . Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Saint Andrew Daily Missal with Vespers for Sundays and Feasts past Dom. Gaspar LeFebvre, O.Southward.B., Saint Paul, MN: The Eastward.Thou. Lohmann Co., 1952, p.1325-1326

- ^ Qur'an 3:52

- ^ Prophet's Sirah by Ibn Hisham, Chapter: Sending messengers of Allah's Messenger to kings, p.870

- ^ Noegel, Scott B.; Wheeler, Brandon M. (2003). Historical Lexicon of Prophets in Islam and Judaism. Lanham, Medico: Scarecrow Printing (Rowman & Littlefield). p. 86. ISBN978-0810843059.

Muslim exegesis identifies the disciples of Jesus as Peter, Andrew, Matthew, Thomas, Philip, John, James, Bartholomew, and Simon

- ^ Musnad el Imam Ahmad Volume four, Publisher: Dar al Fikr, p.72, Hadith#17225

- ^ "John, Son of Zebedee". wwwchurchofjesuschrist.org.

- ^ Doctrine and Covenants 27:12

- ^ a b "John", KJV (LDS): Bible Lexicon, LDS Church, 1979

- ^ a b c d James Hall, "John the Evangelist," Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, rev. ed. (New York: Harper & Row, 1979)

- ^ Sources:

- James Hall, Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, (New York: Harper & Row, 1979), 129, 174-75.

- Carolyn S. Jerousek, "Christ and St. John the Evangelist as a Model of Medieval Mysticism," Cleveland Studies in the History of Art, Vol. 6 (2001), 16.

- ^ a b c d "Saint John the Apostle". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Chicago, Illinois: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 4 Baronial 2017.

- ^ Jadranka Prolović, "Socrates and St. John the Apostle: the interchangеable similarity of their portraits" Zograf, vol. 35 (2011), 9: "Information technology is hard to locate when and where this iconography of John originated and what the epitome was, withal it is clearly visible that this iconography of John contains all of the chief characteristics of well-known antique images of Socrates. This fact leads to the conclusion that Byzantine artists used depictions of Socrates as a model for the portrait of John."

- ^ J.Thou. Elliot (ed.), A Drove of Counterfeit Christian Literature in an English Translation Based on M.R. James (New York: Oxford Academy Press, 1993/2005), 343-345.

- ^ *James Hall, Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Fine art, (New York: Harper & Row, 1979), 129, 174-75.

- Jeffrey F. Hamburger, St. John the Divine: The Deified Evangelist in Medieval Fine art and Theology. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), xxi-xxii; ibidem, 159-160.

- Carolyn Southward. Jerousek, "Christ and St. John the Evangelist as a Model of Medieval Mysticism," Cleveland Studies in the History of Fine art, Vol. 6 (2001), sixteen.

- Annette Volfing, John the Evangelist and Medieval Writing: Imitating the Inimitable. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 139.

- ^ *Jeffrey F. Hamburger, St. John the Divine: The Deified Evangelist in Medieval Fine art and Theology. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), xxi-xxii.

- Carolyn S. Jerousek, "Christ and St. John the Evangelist as a Model of Medieval Mysticism" Cleveland Studies in the History of Art, Vol. 6 (2001), 20.

- Sarah McNamer, Melancholia Meditation and the Invention of Medieval Compassion, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Printing, 2010), 142-148.

- Annette Volfing, John the Evangelist and Medieval Writing: Imitating the Inimitable. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 139.

- ^ *Carolyn Due south. Jerousek, "Christ and St. John the Evangelist equally a Model of Medieval Mysticism" Cleveland Studies in the History of Art, Vol. half dozen (2001), 20.

- Annette Volfing, John the Evangelist and Medieval Writing: Imitating the Inimitable. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 139.

- ^ Sarah McNamer, Melancholia Meditation and the Invention of Medieval Compassion, (Philadelphia: Academy of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), 142.

- ^ Sarah McNamer, Affective Meditation and the Invention of Medieval Compassion, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), 145.

- ^ Sarah McNamer, Affective Meditation and the Invention of Medieval Compassion, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), 142-148.

- ^ Richard Dorment (15 February 1997). "The Sacred and the Sensual". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 26 February 2016.

Sources [edit]

- Coogan, Michael; Brettler, Marc; Newsom, Ballad; Perkins, Pheme (ane March 2018). The New Oxford Annotated Bible: New Revised Standard Version. Oxford University Press. p. 1380. ISBN978-0-19-027605-viii.

- Lindars, Barnabas; Edwards, Ruth; Court, John Grand. (2000). The Johannine Literature. A&C Black. ISBN978-ane-84127-081-4.

- Perkins, Pheme (1998). "The Synoptic Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles: Telling the Christian Story". In Barton, John (ed.). The Cambridge companion to biblical interpretation. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN978-0-521-48593-7.

- Perkins, Pheme; Coogan, Michael D. (2010). Brettler, Marc Z.; Newsom, Ballad (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible: New Revised Standard Version. Oxford University Press. p. 1380.

- Ruddy, Mitchell (2011). An Introduction to The Gospels. Abingdon Printing. ISBN978-1426750083.

External links [edit]

- Eastern Orthodox icon and Synaxarion of Saint John the Apostle and Evangelist (May eight)

- John the Campaigner in Art

- John in Art

- Repose of the Holy Apostle and Evangelist John the Theologian Orthodox icon and synaxarion for September 26

- Works by John the Campaigner at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about John the Campaigner at Internet Annal

- Works past or nearly Saint John at Internet Archive

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_the_Apostle

0 Response to "Hall James Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art 2nd Ed"

Post a Comment